The Privacy Law “State of Play” In 2024

As we embark on 2024, privacy law continues to advance, particularly, here in the United States, a state-by-state regulatory patchwork is forming. Though there are core themes in common throughout practically all the newly passed state comprehensive privacy laws, critical differences must be accounted for. The result is a “balkanized” compliance landscape, resulting in a challenge for businesses seeking to meet their obligations under applicable privacy laws. Here, we overview some of the most notable developments in the privacy law “state of play” in 2024.

The “Balkanized” State-By-State Privacy Law Landscape

When we wrote our “Privacy Law 2023 “State of Play,” only five states with comprehensive privacy laws were in effect or were to go into effect – California, Utah, Connecticut, Colorado, and Virginia. Since then, we have seen the passage of comprehensive privacy laws in over a dozen states. With the 2024 election season in full swing and partisanship at a fever pitch, there is broad consensus that it will be nearly impossible for lawmakers to pass a comprehensive federal privacy law prior to the election in November 2024. Though there are calls from NGOs such as EPIC to enact a federal privacy law, as things currently stand, businesses must contend with the fragmented patchwork of laws and formulate a compliance strategy corresponding to obligations imposed under the regulatory frameworks to which they are subject.

As noted, more than a handful of states currently have comprehensive privacy laws, some in effect and some that will go into effect. For those states with laws passed but not in effect, the effective dates range from 2024 to 2026. The good news is that for organizations who have compliance programs that address requirements under the currently in effect laws, such as California (CPRA/CPRA), Colorado (CPA), Connecticut (CTDPA), Utah (UCPA), and Virginia (CDPA), much of the “heavy lifting” is likely to have been completed and a review and potential nuanced changes may be in order.

Moving toward future laws, later in 2024, Texas, Oregon, Florida, and Montana will go into effect. Texas’ comprehensive privacy laws are particularly unique compared to those of other states, as they apply to almost all except unclearly defined “small businesses.” On the other hand, Florida’s law will only apply to very large businesses, specifically those with at least $1 billion in annual revenue and engaging in certain lines of business. Additional laws will come into effect in 2025, including Delaware (January), New Hampshire (January), New Jersey (January), and Tennessee (July).

The Common Themes That Generally Run Through The State Laws

While it is important to be cognizant that there are nuances to each state’s comprehensive privacy laws, several key common themes generally run throughout and include the following:

- Extraterritorial: The laws are extraterritorial, as they apply when offering products and services to a state’s consumers, but the entity itself does not have to be within the state to be within its scope.

- Thresholds: The laws have general thresholds of a certain amount of personal information processing, revenue, or specifics regarding selling personal information, so they generally may not apply to very small entities. Note that even an IP address is considered personal information, so the thresholds can be met more easily than one might imagine.

- Nonprofits: Some laws exempt nonprofits, but others apply to both for-profit businesses and nonprofits alike.

- Exemptions: Several of the laws exempt the data or, at times, the entire entity (entity-level exemption vs. only data-level) if they are subject to federal laws (federal preemption) such as HIPAA and GLBA, among others.

- Sensitive Data: The laws provide additional protections for sensitive data. Still, some require “opt-in consent” prior to processing such data, whereas others do not require consent but allow consumers to opt out of such processing.

- Obligations: The fundamental obligations under the laws include providing notice about the processing of personal information (a Privacy Policy), data minimization and retention schedules, reasonable cybersecurity of data, assessments of risk in specific contexts, compliance with processing consumer privacy rights requests, implementing data processing agreements, and prohibitions on discrimination for the exercising of one’s privacy rights.

- Privacy Rights: Privacy rights under the laws generally include notice, access, deletion, portability, correction, the right to opt out of processing for targeted advertising, automated decision-making and profile, and the sale of personal information. Opt-in consent may be required for the processing of sensitive data and children’s data.

- Enforcement: The laws are generally enforced by a dedicated agency such as the CPPA in California or the state attorneys general, with a private right of action only in limited circumstances, as in the case of CCPA/CPRA “lack of reasonable security” as well as Florida’s unique law aimed only at very large companies.

Key Areas To Review For Compliance With New Laws

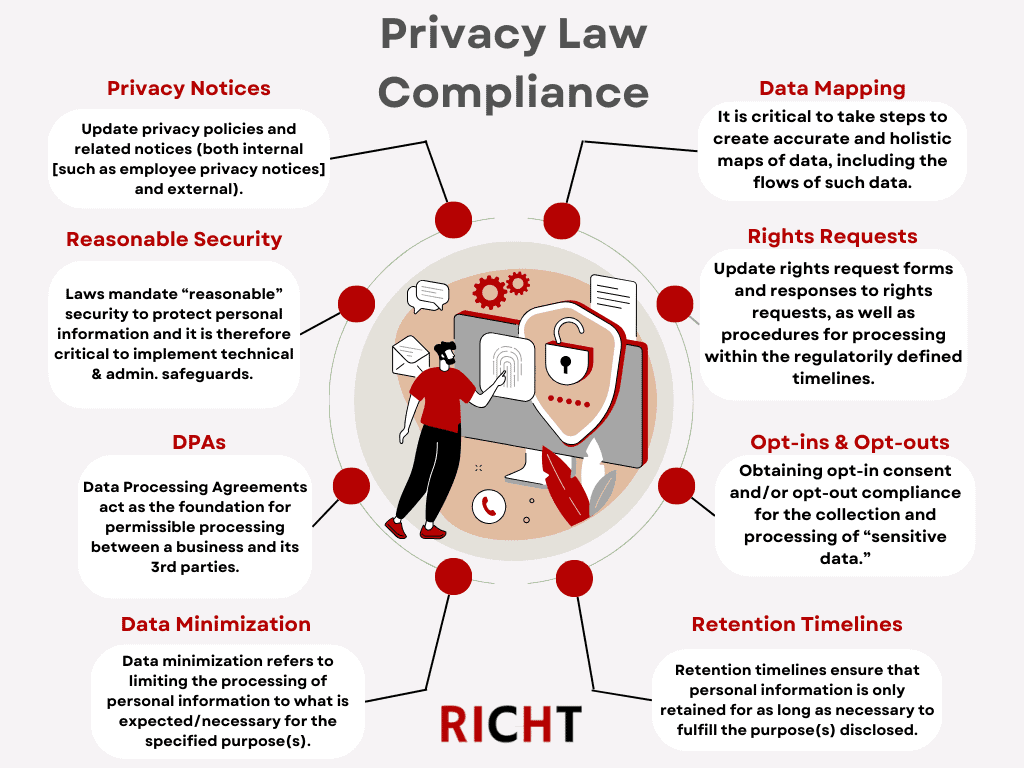

While there are themes that run throughout all of the comprehensive privacy laws, key steps for compliance to review and prepare for concerning the new wave of entrants include the following:

- Privacy Notices: Updating privacy policies and related notices (both internal [such as employee privacy notices] and external).

- Rights Requests: Updating rights request forms and associated template responses to data subject access requests (DSARs), among other rights requests, as well as procedures for processing within the regulatorily defined timelines.

- Opt-ins & Opt-outs: Obtaining opt-in consent and/or opt-out compliance for the collection and processing of sensitive data (what is “sensitive” is regulatorily and, at times, uniquely defined in each law).

- Data Mapping: Knowing what personal information is being processed plays a foundational role in properly complying with privacy and data protection laws. Therefore, it is critical to take steps to create accurate and holistic maps of data, including the flows of such data.

- Data Processing Agreements (DPAs): DPAs are essential components of a comprehensive privacy law compliance program as they are generally required under comprehensive state and international laws and act as the foundation for permissible processing between a business and its vendors and other third parties.

- Data Minimization & Retention Timelines: Data minimization refers to limiting the collection and processing of personal information to what is expected and necessary for the specified purpose(s). Retention timelines ensure that personal information is only retained for as long as necessary to fulfill the purpose(s) disclosed. Both data minimization and retention timelines aim to restrict the broad use of personal information and secure said data.

Compliance in such a dynamic and fractured privacy law landscape can be overwhelming, especially for an organization just embarking on the journey. It is, therefore, essential to identify the common throughlines of practically all the laws, including vis-a-vis international frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Perfection in this regard should not be the goal to the extent that it hinders progress toward compliance. It is critical to balance risk with resources. What is deemed satisfactory from a compliance perspective for a large multinational will be wholly different from what compliance looks like for a new e-commerce store.

“Sensitive Data” Is An Area Increasingly In Focus

Sensitive data is a regulatorily defined term under comprehensive privacy laws, whether in the context of state laws in the United States or across the ocean in jurisdictions such as the European Union or the United Kingdom subject to the GDPR or similar regulations. Outside the comprehensive privacy law-specific context, sensitive data is also in focus on the federal level, as is illustrated by the President’s Executive Order “to protect Americans’ sensitive personal data from exploitation by countries of concern.” The FTC is also increasingly aggressive in policing privacy, including children’s health, browsing, and location data.

While the nuances of what is deemed “sensitive” vary, the general rule is consistent. For personal information that is particularly “sensitive,” compliance obligations are added. The specifics of these additional protections will range, but they may include additional security, consent, opt-in, or opt-out, among other requirements.

Below, we overview two common kinds of sensitive data, children’s and health data, and highlight how various new laws approach such processing. However, there are many other kinds of sensitive data types. Some of the most commonly included categories of personal information deemed sensitive by privacy laws include the following:

- Biometrics

- Citizenship and immigration information

- Genetics

- Precise geolocation data

- Racial or ethnic origin

- Religious beliefs

- Sexual orientation

- Precise geolocation data

Children’s Data

Historically, regulators have focused on the dangers of the processing of children’s data, such as via legacy laws like the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). That said, with children increasingly spending time online, there is even greater scrutiny and an impetus for instituting additional protections emanating from both the state and federal levels. Note though, that depending on the law, the definitions and obligations about what what age is deemed to be a “child” and therefore subject to additional protections, varies.

On the state law front, for example, Connecticut’s privacy law includes additional measures for handling the personal information of those between the ages of 13-17. Other laws outside the comprehensive privacy law context come in the form of social media laws and focus on protecting children on social media platforms. The states that have passed such laws include Utah, Louisana, California (Age Appropriate Design Code Act), and Florida. The laws vary in their requirements, but the components may include verifiable parental consent, content moderation, and “age-appropriate design.”

On the federal side, the FTC has issued a notice of proposed rulemaking to update the COPPA Rule as it has not been updated. The FTC last made changes to the COPPA Rule in 2013, which, in terms of new developments and the pace of technological advancement, may as well have been forever ago.

As the laws concerning children’s data are very dynamic, it is important to account for children’s personal information processed and how the emerging patchwork privacy law dynamic applies. Particular focus should be on any sharing or sale of children’s personal information, including for targeted advertising, as well as any required parental consent.

Health Data

While the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) covers certain data concerning one’s health, there is a significant chasm concerning data that is “sensitive” health-related information but not within the scope of HIPAA. In light of this gap, and because of concerns amongst some about ramifications for the processing of such health data, including post the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, certain states, as well as regulators such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), have been passing laws and putting out guidance to make it clear that such health data is subject to greater protection.

Washington’s My Health, My Data Act

One of the most notable developments relating to health data is Washington’s landmark and broad My Health, My Data Act (MHMD), which changed the health data privacy paradigm in significant ways. Set to go into effect at the end of March 2024, the MHMD is concerningly vague and applies to “consumer health data” but, notably, due to lack of specificity in drafting, goes beyond the traditional understanding of what health data is. Specifically, the law states that “consumer health data” is “personal information that is linked or reasonably linkable to a consumer and that identifies the consumer’s past, present, or future physical or mental health status.” It then goes on to list examples of such data, including the following:

- Individual health conditions, treatment, diseases, or diagnosis.

- Social, psychological, behavioral, and medical interventions.

- Health-related surgeries or procedures.

- Use or purchase of prescribed medication.

- Bodily functions, vital signs, symptoms, or measurements of the information described in this subsection (8)(b).

- Diagnoses or diagnostic testing, treatment, or medication.

- Gender-affirming care information.

- Reproductive or sexual health information.

- Biometric data.

- Genetic data.

- Precise location information that could reasonably indicate a consumer’s attempt to acquire or receive health services or supplies.

- Data that identifies a consumer seeking health care services.

Notably the law is triggered even when only collecting consumer health data, even if not used. This contrasts with more specifically drafted laws regulating health data, such as those in Nevada, where use is necessary to trigger the law’s application.

The law also has a “geofencing ban,” which prohibits certain location detection technologies around healthcare-related facilities. New York, Connecticut, and Nevada have similar laws aimed at deterring such geofencing activities, though there are nuances to each law.

For those organizations within the scope of the MHMD, a fairly significant compliance undertaking will be necessary. Further, the law includes a private right of action, a departure from most other comprehensive state privacy laws, and substantially raises the stakes. On the compliance side, the law requires a standalone health data privacy notice, getting consent prior to collecting, disclosing, or selling consumer health data, and providing users with a variety of rights. Given the broad nature of Washington’s law, it is important to audit processing activities with a particular focus on whether any sort of profiling or targeting is done that involves health in even the most general sense.

Consent In The Context of Sensitive Data Generally

Though consent is not required in certain jurisdictions for the processing of sensitive information, as a strategy to accomplish “broad compliance” with all laws and as a matter of best practice, consent for the processing of sensitive data is generally advisable. Consent should have the following essential components:

- Consent should be attained via a consumer’s clear, unambiguous, and affirmative act.

- Consent should be freely given, informed, and specific.

Data Processing Agreements

Data processing agreements (DPAs) play a leading role in a robust privacy program. A DPA outlines the roles, responsibilities, and scope of processing and is a requirement under an increasing number of comprehensive privacy laws. DPAs, combined with data mapping and vendor risk assessments, ensure visibility, accountability, and security for the varying kinds of processing activities that an organization undertakes via vendors and, in particular, service providers.

Many privacy laws, such as California’s CCPA, as amended by the CPRA, require certain clauses in DPAs. Therefore, DPAs need to be audited and regularly updated to account for additional language that may be required after new laws are passed.

Some of the key general components of DPAs include the following:

- The nature and purpose of processing;

- The type(s) of personal data to be processed by the vendor;

- The rights and responsibilities of the parties;

- The duration of and termination procedure concerning the processing;

- Ensuring both adequate technical and administrative safeguards in relation to the personal data processed, including as it relates to ensuring employees of the vendor, as well as any third parties, are required to maintain the confidentiality of the data;

- Ensuring that any subcontractors or other third parties that the vendor wishes to engage meet certain threshold criteria and potentially even require pre-approval or rights to object;

- Implement audit rights and procedures for exercising said audit, including as it relates to a demonstration of compliance; and

- Ensuring that the vendor and any of their subcontractors or third parties will assist with the deletion of data as well as any other privacy rights requests.

Beyond the general inclusions, as mentioned previously, states and countries have particular clauses that may have to be included in a DPA. For example, California’s CCPA, as amended by the CPRA, requires the following:

- Prohibition against service providers “selling” or “sharing” personal data;

- Specifying the business purpose of the processing;

- Prohibition against service providers from retaining, using, or disclosing personal data for their own purposes (subject to certain exceptions);

- Requiring the vendor to comply with the CCPA as amended by the CPRA;

- Granting audit and other rights to the business to ensure service providers’ compliance;

- Requiring notification if the service provider can no longer meet its obligations under the CCPA as amended by the CPRA; and

- Rights request compliance.

Additional key aspects of DPAs include indemnification and limitations of liability clauses and notification timelines concerning incidents and obligations in the event of a data breach.

Vendor Risk Assessments

At the outset of exploring a relationship with a vendor, risk assessments from various perspectives need to be undertaken. These involve security and privacy, including as it relates to ensuring best practices and compliance, and form the bedrock of a compliance program. After all, according to a report, 62 percent of data breaches are due to vendors. With the immense cost brought about by data breaches, both in the monetary sense and also reputationally, doing everything possible to avoid such an event is a priority. Ensuring vendors are vetted and continually monitored goes a long way in achieving this risk mitigation. On the compliance side, such review is critical beyond just the breach perspective, as regulators are showing intention to hold businesses responsible for outsourced potentially non-compliant activities, and in particular in the more sensitive areas of processing such as targeted advertising, data scraping, as well as when selling or sharing personal information. In line with this, when seeking to engage a vendor, having the conversation about how they account for compliance in their “higher-risk” data processing should not be shied away from. If answers are unsatisfactory, even for a very tempting service that will be valuable to the business, beginning a relationship with such a vendor could bring about real costs down the line. Further, for any risk identified as part of a vendor risk assessment that is deemed to be “an acceptable risk,” it is critical that such risk is documented, monitored, and mitigated on an ongoing basis. In addition, ensuring vendor compliance with the processing of data access and other privacy rights requests is also essential, as they are often “the missing piece of the puzzle” when it comes to operationalizing such requests, particularly as it concerns deletion.

Regulators are increasingly focused on data processing that may not even be traditionally thought of as sensitive per se, and a great example of this is the restrictions on targeted advertising (referred to as “cross-contextual behavioral advertising” under some laws) as well as the rights afforded to consumers concerning such processing. The reasons for this added focus and, hence, more stringent obligations and protections are varied and, to some extent, disputed. At the most basic level, targeted advertising has the potential to track and build in-depth personas of individuals across websites, with the associated personal information potentially being “shared far and wide.” That said, there are also potential political goals and vendettas, including those related to the “bad rap” that large social media and big tech companies, which are also the largest players in targeted advertising, have accumulated over the years. Regardless, such use of these technologies and associated processing results in compliance obligations.

Cookies, Pixels, & Related Technologies

Cookies, pixels, and related technologies, such as software development kits (SDKs), are the main ways that targeted advertising is conducted. There is great technical nuance when it comes to each, such as 1st party vs 3rd party cookies, and the differences can have significant compliance obligations. It is, therefore, essential to take an inventory of all such technologies being utilized and to document how and what they are doing, including the associated data flows as well as the agreements that govern each of the relationships from the vendors providing said technologies. After all, some of the cookies may be bonafide “service provider” relationships with less burdensome compliance obligations, such as those concerning processing opt-outs, while others, such as targeted advertising cookies and the vendors providing them, will in all likelihood be deemed a “sharing” that is subject to potential opt-out or opt-in compliance.

Beyond considerations concerning compliance with the law, pixels and similar technologies also offer a “convenient” vector for “drive-by” lawsuits from the plaintiffs’ bar. For context, In 2023, there were 265 lawsuits filed against various big tech behemoths ranging from Meta to Alphabet for their pixels and tagging managers, an 89% increase from the year prior. A notable case in this regard is John Doe v Meta Platforms Inc., which alleges that the use of Meta’s pixel breached the privacy of individuals who accessed certain health providers’ websites that tracked and sent data about such web visits to Meta.

Opt-Outs, Universal Opt-Out Mechanisms, & The Global Privacy Control

As a corollary of cookies and related technologies concerning opt-out and opt-in obligations under various laws requiring a “Do Not Sell Or Share My Personal Information” or “Your Privacy Choices” link and icon, some laws go even further and mandate honoring of “universal opt-out mechanisms” or “UOOMs.” In the most basic terms, UOOMs allow individuals to configure their browser or device to automatically communicate their preferences to websites and applications, including when it comes to opting out of targeted advertising as well as other cookie and tracker blocking. The technology allows for seamless communication about what a user’s wishes are concerning the processing of their personal information without having to make those choices on a per-website or application basis. This is attractive for privacy regulators and consumers, as it provides a very user and privacy-friendly option. For businesses, though, it is currently quite an undertaking and raises a host of very nuanced questions. First, currently, there is a fragmented landscape about how and which UOOMs to honor. The most common and well-known UUOM is the Global Privacy Control, and it is seeing increased adoption, including being one of the mandated UOOMs under Colorado’s comprehensive privacy law. Conundrums such as what is to be done vis-a-via if a user communicates their preferences via a UOOM on one device and then uses another device that is not recognized are addressed in some laws, such as California’s CCPA as amended by the CPRA, but the challenges are still present.

Biometrics

Biometrics are a unique and increasingly heavily regulated kind of personal information, whether it is protections for such kinds of information under comprehensive privacy laws or biometric-specific privacy laws such as Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), a particularly litigious and plaintiff-friendly law. These kinds of broad biometric laws, and particularly laws such as BIPA that have a private action, pose significant risks if engaging in the collection and other processing of biometrics without proper compliance measures, and in particular, consent. Any facial mapping is a common pitfall. For example, Meta agreed to a nearly $70 million settlement on account of such a facial matching feature utilized on its Instagram property.

The new batch of state comprehensive privacy laws also have biometric-specific components. For example, the Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), which went into effect on July 2023 and complemented by regulations promulgated by the Colorado Attorney General, requires that those entities processing certain biometrics are required to perform an annual audit.

To illustrate, under the CPA, biometrics are defined as follows:

“Data generated by the technological processing, measurement, or analysis of an individual’s biological, physical, or behavioral characteristics that can be Processed for the

purpose of uniquely identifying an individual, including but not limited to a fingerprint, a voiceprint, scans or records of eye retinas or irises, facial mapping, facial geometry, facial templates, or other unique biological, physical, or behavioral patterns or characteristics.”

The audit requirement is as follows:

“Biometric Identifiers, a digital or physical photograph of a person, an audio or voice recording containing the voice of a person, or any Personal Data generated from a digital or physical photograph or an audio or video recording held by a Controller shall be reviewed at least once a year to determine if its storage is still necessary, adequate, or relevant to the express Processing purpose. Such assessment shall be documented according to 4 CCR 904-3, Rule 6.11.”

In light of the complex and nuanced legal landscape of biometric processing, it is essential to tread carefully if engaging in such activity. Further, biometrics in the context of employee monitoring is a common use case, and brings with it additional scrutiny.

Privacy Impact Assessments

Assessments to evaluate various kinds of privacy risks have been a mainstay of privacy laws, including under “first mover” frameworks such as the GDPR. State comprehensive privacy laws in the United States, such as California and Colorado, among others, are following suit and also requiring privacy risk or impact assessments in certain scenarios. Sometimes referred to as Data Privacy Impacts assessments (DPIAs) or simply Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs), the assessments are generally mandated for more sensitive processing activities. The assessments accomplish both an exercise in aiming to uncover and balance risks and how to mitigate accordingly as well as to ensure accountability, including in the event of some sort of enforcement action. After all, the assessments can generally be requested by regulators and, in some instances, need to be proactively provided. Some of the common processing types that require PIAs include targeted advertising, sale of data, automated decision-making, and profiling, as well as other kinds of processing of sensitive data such as genetics.

Dark Patterns

“Dark patterns” is a broad “catch-all” classification of practices that regulators deem to be “manipulative” interfaces and designs that somehow “unfairly trick” the user and their decision-making, in particular as it relates to their privacy choices. The issue with dark-pattern regulation is that it is subjective in some respects and can be a useful cudgel for regulators to leverage against the “unpopular (or unlucky) flavor of the day.” That said, there are objective and more clearly “dark patterns” that should be avoided. These include pre-checked boxes or choices, using very small disclosure text, differing button highlights, or color contrasts to influencer choice, among others. States such as California and Colorado regulate dark patterns as part of their comprehensive privacy laws, but other regulators, such as the FTC, have signaled a focus on regulating such practices under their broad Section 5 mandate.

Artificial Intelligence Everywhere

Artificial intelligence (AI) and its broad-ranging application to a host of business processes, including as it relates to consumer-facing offerings, continues to proliferate. As a result, regulators are increasingly exploring ways to regulate the powerful technology. The EU has passed the AI Act, and states in the United States are passing laws as well. Federal regulators in the United States are also putting out rulemaking, including the FTC. Privacy law is particularly relevant to AI law due to the various cross-overs, including the large data sets that power AI models. As AI technology emerges, we expect more stringent compliance obligations. That said, the current prudent approach is to ensure data processing implications are explored, including via robust DPAs implemented with any AI providers, as well as AI acceptable use policies, and also ensuring proper disclosures when using AI in consumer-facing offerings.

Ancillary But Particularly Litigious Areas

Though outside the scope of “bread and butter” privacy law, we want to bring attention to several areas of current focus by “shakedown-style” plaintiffs’ lawyers. Similar to the strategy used in the hallmark “ADA website compliance lawsuits,” these new claims concern chatbots, pixels, and session recording tools. The pixel lawsuits claim that there is some unlawful sharing of information, and in particular, it concerns the sharing of health information. The chatbot claims center on the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA) and alleges that since the service provider of the chatbot may have access to the chats, there is a wiretapping violation. Lastly, the session recording private actions allege violations of wiretapping statutes and the Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA), which prohibits a videotape service provider from knowingly disclosing any of their user’s personal information. For all of these aggressive and potentially even frivolous claims, ensuring explicit consent and at least prominent disclosures regarding the nuances of these kinds of data processing will go a long way toward avoiding these types of lawsuits. That said, generally, the lawyers running these “lawsuit factories” are counting on quick settlements so they can proceed to their next targets.

Telemarketing & Text Messaging

Text messaging, particularly in the marketing context, holds significant potential and has seen widespread adoption among businesses of all types and sizes. Whether it be transactional texts concerning an order confirmation or update or notifications about an upcoming promotion, text messaging is unparalleled in terms of deliverability and the intended recipient actually viewing the message. That said, the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA), state laws, and self-regulatory organizations such as those involved in A2P 10DLC make compliance a critical component for success and for avoiding risk and subsequent costs. Telemarketing, while more niche and less commonplace in today’s digital-first world, also has its nuances and compliance obligations. States, including Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington, have new laws that have ramifications in this regard. Relatedly, the FCC has closed the “lead generator” loophole and now requires “one-to-one” consent. Now, lead generators will have to obtain “prior express written consent” “for one seller at a time – rather than have a single consent apply to multiple telemarketers at once.”

Going Forward

With privacy law and ancillary areas such as artificial intelligence law moving at such a feverish pace, finding a clear path toward achieving compliance can be a daunting task. This is especially true for organizations with a nascent privacy compliance program. Since privacy law is not going anywhere, and more and more jurisdictions are passing comprehensive laws aimed at protecting their constituencies’ personal information, we advise clients to at least begin the compliance journey. Granted, the process is iterative, will take time, and there will be challenges. However, as a compliance program becomes more mature, each subsequent “lift” in response to a new legal framework or regulatory guidance will be incrementally less complicated. With a team that is adequately trained in privacy compliance fundamentals and implements privacy best practices, an organization minimizes legal risk and associated costs and can turn privacy into a competitive advantage.