The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

On May 25, 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a broad-ranging European Union regulation governing data protection and privacy, went into effect, changing the privacy regulatory framework in monumental ways. It continues to make its mark by acting as a template for new privacy laws and imposing challenging compliance requirements on organizations of all stripes and sizes.

In many ways, the GDPR was a critical development beyond the immediate legal compliance ramifications. It signaled clearly how regulators, corporations, and the citizenry are shifting their views on privacy rights and the laws that safeguard them. While there were a host of statutes regulating data and privacy before the GDPR, some on the books for decades, the GDPR changed everything in monumental ways.

It would be myopic to view the effects of the GDPR solely in terms of the immediate consequences relating to arduous compliance obligations mandated by the law. While the new regulation has undoubtedly impacted the C-Suite, needing to allocate substantial resources to compliance, its effects are more far-reaching. The GDPR “opened the gates” for governments worldwide to follow the EU’s lead. The prevailing view is that regulators will take an accelerated and more aggressive approach to guard their citizenry’s privacy and data, and that they will use the GDPR as their template, including comprehensive privacy laws being passed in the United States, such as California’s CCPA as amended by the CPRA.

A Wide-Ranging Scope

The GDPR is wide-ranging in its scope, covers diverse topics, and places new obligations on entities in practically every sector. For historical context, the GDPR superseded a previous EU regulation from 1995, known as the “Data Protection Directive” (DPD). In comparison to the DPD, the GDPR is considerably more stringent in numerous ways. Notably, it vastly expands on what data is considered Personally Identifiable Information (PII). Such an expansion is significant because it increases the burden on those entities that may have previously collected data that was not subject to EU regulation. For example, IP addresses would fall under the purview of GDPR as they are classified as PII (and thereby protected). In contrast, previously, under the DPD, IP addresses would not have had such a classification.

The GDPR also departed from past law in another consequential way. It considered organizations subject to the data protection framework of GDPR regardless of domicile. The only requirement for the new regulations’ applicability is that an organization collects the PII of persons in the EU.

It is essential to point out that GDPR regulates the data of all those in the EU and not just citizens. As Recital 14 states, “[t]he protection afforded by this Regulation should apply to natural persons, whatever their nationality or place of residence, concerning the processing of their personal data.” With that said, individuals living outside the EU are not within the regulatory scope of the EU’s GDPR, even though they might be citizens of an EU member state. In that context, if a citizen of Germany travels to the United States and provides personal information to a company, such processing may very well not be regulated under the GDPR unless there are other relevant factors, such as processing in the EU.

What Is Considered Personal Data?

GDPR defines personal data as:

‘Personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.

Art. 4 GDPR

The definition makes clear that the kind of data regulated is quite broad in scope and encompasses information that, under previous regulations, was deemed more “benign.” With that said, the GDPR only “applies to the processing of personal data wholly or partly by automated means and to the processing other than by automated means of personal data which form part of a filing system or are intended to form part of a filing system.” While this encompasses almost all processing activities, there are important exceptions.

There is a litmus test under the GDPR to determine whether data is within the scope of the framework. The general rule is that data is regulated if it can lead to the identification of a person. Nuance is crucial here, since although a specific data point alone may not lead to potential identification or have intrinsic value, it may still be within the purview of GDPR. The reason for this is based on the nature of data since, in the aggregate, a single (seemingly useless) data point can help lead to the identification of an individual.

An example to illustrate this point may be helpful. If Facebook only had a user’s email address that perhaps did not include their name, the value of that email address alone might be of limited value and not hold any potential for identifying the email owner. Simultaneously, if, in conjunction with the email address, Facebook also collected the user’s IP address and name, among a whole host of other data points, that formerly referenced anonymous email address would help identify the person. The drafters of the GDPR took an approach that was cognizant of this reality. Therefore, data is analyzed from a bird’s eye view that assesses the effect that a conglomeration of information can have on a person’s privacy rights. So what are some examples of PII regulated under the GDPR?

- Names

- Health data

- Genetic & biometric data such as device fingerprints

- IP addresses

- MAC addresses

- Cookie identifiers

- Personalized email addresses

The listed examples are only some of the most common forms of data deemed to be PII. Many other, less obvious pieces of information fall under the purview of the GDPR too.

With such a broad view of PII undertaken under the GDPR, it is important to know what does not fall under this all-encompassing approach. Some data that is not considered PII includes generic business email addresses such as [email protected] or fully anonymized data.

In terms of anonymized data not being considered to be PII, it is necessary to stress a technical point. Encrypted, pseudonymized, or anonymized data where reversibility is possible and can, therefore, lead to potential identification is considered to be protected PII.

Data Privacy Vs. Data Protection

Contrary to popular belief, the GDPR is not a privacy regulation per se. More accurately, the GDPR is a data protection regulatory framework. The word “privacy” is only mentioned a single time in the entirety of the GDPR.

With that said, there are many ways that the GDPR improves the protections for individual privacy, nonetheless. That is due to the core similarities and overlap between what constitutes data protection and privacy. In many ways, these terms are synonymous, but it is essential to remember that they are not identical. Data protection concentrates more exclusively on how data can be collected, stored, used, and exchanged, while data privacy focuses more on individuals’ privacy rights.

Intersection of GDPR & ePrivacy

As we mentioned previously, the GDPR has its square focus on data protection and processing. Though there is much overlap between data protection, processing, and privacy, there are laws in the EU that specifically address privacy. The ePrivacy Directive of 2002, colloquially known as the “Cookie Law,” is one such privacy-focused legal framework. With that said, it is intimately related to and highly applicable to the GDPR. In large part, that is because the Directive is lex specialis to the GDPR. That means that the Directive, in many ways, interprets the core tenets of the GDPR.

Of significant note is that the ePrivacy Directive was set to be overhauled by what was known as the ePrivacy Regulation. However, the ePrivacy Regulation is no longer under consideration, as the European Commission withdrew it from its work programme for 2025 due to a lack of foreseeable agreement.

Controllers Vs. Processors

The GDPR introduced several new definitions to the privacy law lexicon to assist in delineating roles and corresponding obligations among the different parties involved in handling PII. One of these is that of controllers and processors. In the words of EU regulators, a controller “determines the purposes for which and the means by which personal data is processed.” On the other hand, a data processor “processes personal data only on behalf of the controller.”

Conceptually, these definitions seem relatively straightforward and clear. However, there are specific scenarios where novel questions arise regarding who gets assigned the label and the associated obligations of the controller or processor. One of the situations where this analysis becomes confusing is in the case of joint relationships. These partnerships are quite numerous, but a pertinent opinion from the EU’s Advocate General and a subsequent court ruling illustrate this.

The case in question involved a fashion website called Fashion ID, which implemented the Facebook “like button” that recorded user activity. The opinion’s rationale focused on the notion that both the website and Facebook were pursuing their own independent, commercial-oriented goals and were therefore deemed to be joint controllers. In the words of Advocate General Michal Bobek:

“Despite the fact that the specific commercial use of the data may not be the same, in general, both the Defendant and Facebook Ireland seem to pursue commercial purposes in a way that appears to be mutually complementary. In this way, although not identical, there is unity of purpose: there is a commercial and advertising purpose.”

In practical terms, because both the website operator and Facebook are each using and exercising control over the PII gathered from users on the website, they each have obligations as data controllers to individuals under the GDPR. Therefore, obtaining consent before the collection or transfer of protected information is required.

On July 29, 2019, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled on this case and agreed with the Advocate General’s rationale, deeming Facebook and the website operator to be joint controllers. In addition to obtaining consent for PII collection, controllers have various additional responsibilities under the GDPR.

Some of the core aspects of these duties are outlined below:

- One of the primary responsibilities is to use easy-to-understand language in notices and policies directed toward data subjects, such as privacy policies and related online terms and conditions. The overarching goal of this duty is to increase transparency and understanding of what individuals are consenting to.

- Data controllers also need to make it possible for data subjects to exercise a host of rights, such as access and to have their information deleted. Sometimes referred to as the right to be forgotten, this right is expansive and open to much contentious litigation and societal debate.

- Portability is also a central theme of the GDPR, which relates to data subjects’ right to move their data among various controllers freely.

- “Privacy by design” and “Privacy by default” are terms of art that underlie much of the rationale behind the GDPR. These terms mandate that the collection, processing, and storage of PII should be undertaken to the minimum degree necessary in light of the circumstances. This area of regulation is quite vague and adds to the uncertainty of adequately meeting compliance standards.

- For some but not all entities, a data protection officer (DPO) appointment is required. Ascertaining whether a DPO is mandated for a specific organization involves a multi-factor analysis that relies largely on the nature of the organization’s business activity at hand.

- The GDPR also imposes an obligation of accountability that mandates data controllers to document processes and policies relating to collecting, processing, and storing protected PII, such as data mapping for processing and privacy impact assessments (PIAs) for certain higher-risk activities.

Grounds For Processing

Under Article 6 of the GDPR, there are six lawful grounds for processing a data subject’s PII. Disclosure of the chosen grounds for lawful processing is required so that there is transparency for data subjects.

The six lawful premises for processing are listed below:

- CONSENT: The data subject gave their consent and said permission is proper. We will discuss what constitutes valid consent under the GDPR further on in this discussion.

- CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATION: When processing of PII is necessary for the performance of a contract in which the data subject is a party.

- LEGAL OBLIGATION: The processing of the subject’s PII is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation.

- VITAL INTEREST: When processing is necessary to protect a data subject’s vital interests or another person’s.

- PUBLIC INTEREST: The processing of the data subject’s PII is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

- LEGITIMATE INTEREST: When processing is necessary for legitimate interests pursued by the data controller or a third party, except when the interests, rights, or freedoms of the data subject override such interests. The legitimate interest rationale for processing is most broad in terms of the kinds of processing it may justify. At the same time, it also requires balancing interests, creating a gray area. Processing under the regime of legitimate interests stands in stark contrast to the processing based on consent, where there is relative definitiveness as to whether the data subject gave permission.

After reviewing the previous six grounds for the lawful processing of PII, two things should be apparent. First, the appropriate grounds for processing depend largely on the nature and rationale for collecting and using protected PII. It should also be clear that a given scenario may offer more than one option to justify PII processing. The most common and frequently discussed grounds that overlap are consent and legitimate interest.

As mentioned, when compared to processing based on consent, which is relatively straightforward, grounds for processing under legitimate interest can get more confusing. Questions surrounding what constitutes adequate legitimacy and what kind of balancing needs to be employed are front and center in the legitimate interest analysis. One of the most helpful ways to gain clarity in this regard is by reviewing the examples included in guidance from various data protection authorities.

If the selection of legitimate interest is the basis for lawful processing, then the GDPR, under its mandates relating to transparency, requires disclosure of the rationale surrounding legitimate interest. Regardless, data subjects can dispute the legitimate interest premise’s adequacy, and controllers would have to justify their rationale further. The requirement may not seem so negative in the grand scheme of things since one of the alternatives, processing based on consent, can be unilaterally withdrawn and cause complexity. With that said, there is a three-step analysis to undertake when employing processing under the legitimate interest rule. Known as Legitimate Interest Assessments (LIA), the goal of the analysis is to balance interests, which is a common theme that runs throughout the GDPR. More specifically, data controllers need to ensure that their interests are not overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of data subjects.

Consent

One of the commonly used legal bases for processing and a hallmark obligation that controllers are subject to under the GDPR revolves around consent. This requirement mandates that getting proper permission from data subjects is a precondition (absent other grounds for processing) for data controllers to collect and use a data subject’s PII. Critically, under the GDPR, consent is only deemed adequate if it is unambiguous, informed, and freely given. The notion that consent is “freely given” has opened up a debate as to what exactly constitutes “freely.” While it is clear that consent must be voluntary, the question remains as to what is deemed to arise to a level of pressure, inappropriate interference, or lack of transparency that thereby renders consent not “freely given.”

To illustrate this contentious issue revolving around consent, we look at a November 2018 decision from the Austrian Data Protection Authority (DPA). The complaint stemmed from the consent options for cookies and related tracking on an Austrian news website.

The publication gave the following choices to visitors when asking for their consent to use cookies and related tracking codes:

- A user could agree to all tracking and cookie use and have free and full access to the website’s content.

- Alternatively, a user could refuse to consent to cookies and any related tracking and have limited access to the publication’s web content.

- The final option offered users the ability to refuse tracking and cookie use and have full access to content in exchange for paying a relatively low monthly subscription fee.

The subsequent complaint to the Austrian DPA argued that these choices were not in line with the requirements of the GDPR since there is no “real choice” and, therefore, no “freely given” consent. This logic rests on the notion that if a user is mandated to accept cookies or is otherwise penalized in the form of limited experience or payment of monies, then such consent is deemed to have been forced upon the user to some degree.

In its decision, the Austrian DPA ruled in favor of the publication. Based on guidance from the Article 29 Working Party (now the European Data Protection Board) relating to consent, the DPA reasoned that the options provided and specifically the choice to pay a low nominal fee did not rise to the level of consequences that would deem consent as not “freely given” and was therefore valid. While this ruling seems quite favorable and welcome for publications offering subscriptions, there is still confusion. In large part, the difficulty is due to the disjointed nature of how specific DPAs of individual EU member states interpret the GDPR. For example, the UK’s DPA, referred to as the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), ruled that the Washington Post’s cookie consent options presented to users did not meet muster. Granted, the WaPo’s options were not identical to those offered by the Austrian publication, but the core theme was the same. The differing opinions on the part of the Austrian and UK DPA illustrate some of the confusion organizations face in achieving GDPR compliance. The complexity in reconciling disparate interpretations of the GDPR among different member states is another example of this recurring issue.

Another important aspect of consent relates to “opt-out consent” vs. “opt-in consent.” The former kind of consent refers to consent based on a default setting or past agreement. Such consent is not considered sufficient under the GDPR. Instead, to process a data subject’s data, an organization must transparently get user consent for that activity.

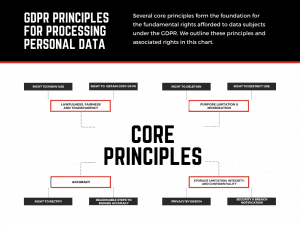

Individual Rights

There are several fundamental rights afforded to individuals under the GDPR, which we summarize below:

- Individuals’ right to be informed on how their PII is used, such as the purposes for processing, retention periods, and with whom the data may be shared. The controller must inform individuals within one month if personal data is obtained from third-party sources, often in the context of personal information collected from the internet. The requirement for notification relating to obtained data is an area holding significant potential risk, and regulators have already issued fines for non-compliance. This right to be informed is at the core of meeting GDPR’s overarching goal of increasing transparency and accountability.

- The right of access gives individuals the right to obtain a copy of their PII.

- The right to rectify under Article 16 of the GDPR gives individuals the right to have inaccurate personal information corrected.

- The right to erasure outlined in Article 17 of the GDPR affords individuals the right to have PII erased, also known as the “right to be forgotten”. This right is wide-ranging but is not absolute and has exceptions.

- Under Article 18 of the GDPR, individuals also have the right to restrict the processing of their personal data. This is an alternative to requesting the erasure of their data. Like the right of erasure, this right is not absolute and carries nuanced exceptions.

- The right to data portability gives individuals the power to move their personal data from one controller to another. Of importance is that this right only applies to data processed under the lawful basis grounds of consent or for a contract’s performance.

- Under Article 21 of the GDPR, individuals have the right to object to the processing of their personal data. This right is nuanced and, like the other rights listed, contains many exceptions and is far from absolute.

- Somewhat of an outlier compared to the previous rights listed, the GDPR affords rights and protections relating to the processing of personal data for automated decisions “that have a legal or similarly significant effect on individuals.” There are additional restrictions for “special category personal data” used in such automated decision-making due to their sensitive nature. This complex area under the GDPR requires a scenario-specific analysis to determine compliance obligations.

These enhanced rights mean businesses need robust systems in place to handle data subject requests quickly and efficiently.

While there are some similarities between some of the listed rights, for the most part, there are important distinctions between them and various nuances that may be relevant in particular scenarios. It is, therefore, imperative for case-specific evaluation, including as it relates to compliance in responding to a request to exercise one of the listed rights.

A Host Of Other Obligations

Depending on the specific scenario at hand, there are a variety of additional requirements that come into effect under the GDPR. These include Data Processing Agreements (DPAs) if a controller engages processors, Data Privacy Impact Assessments (DPIAs), Record of Processing Activities (ROPAs), and the appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO), among others.

Are Cookies The New Monster?

Within the very dynamic world of privacy law, there is substantial confusion around the requirements surrounding cookies. At least in part, this is due to the numerous different kinds of cookies and the disparate treatment they get from regulators. For example, tracking cookies, often employed for targeted advertising activity, are deemed more nefarious and suspect than strictly necessary cookies.

One of the core gray areas is whether cookies employed on a website or other platforms require detailed disclosure. In terms of the law, as it stands in the EU, the prevailing approach among data Protection authorities is that while individual cookie names do not need to be listed, the cookie category and purpose do need to be disclosed transparently.

Another area we see confusion center around is whether the option to block cookies via a toggle or other similar feature is required. The technical blocking of cookies via an in-app (or website) tool is not required. Instead, the requirement is that proper consent to use cookies be acquired or, alternatively, the option to block cookies be provided.

Requirements concerning the use of cookies were expected to be clarified by the ePrivacy Regulation, intended to replace the current ePrivacy Directive. Still, as we mentioned earlier, these plans have been delayed numerous times. Much additional clarity surrounding cookies was expected once the new Regulation came into effect, though this development is no longer anticipated.

Until there is further legislative movement, informed consent should be acquired before utilizing any cookies or collecting PII. As has become common, the most streamlined way of achieving compliance relating to cookies is to have a notice prominently displayed on digital properties. The listing of the cookies in use and what data they collect should be outlined clearly. Finally, and most importantly, allow users to provide, decline, or withdraw consent relating to the use of cookies or the collection of their PII. An ancillary issue that comes up with cookies surrounds the necessity of installing a cookie to remember the consent or lack thereof of the data subject, which becomes an issue if the user declines to accept cookies. In this evolving landscape, regulators may show understanding if there is a good-faith effort made toward compliance.

Policies & Procedures Go A Long Way

One of the central themes emerging out of the GDPR and similar legislation is the importance and necessity of clearly outlined and “battle-tested” policies and procedures. While it is impossible to predict every eventuality, organizations that implement best practices around data hygiene, cybersecurity, and data breach incident response are far better positioned to avoid large-scale issues and mitigate the damage of events that do occur.

As per the GDPR, organizations are required to document how personal data is managed and protected. They are also obligated to provide notice to regulators of a breach within 72 hours. Procedures to comply with these duties and the eight core rights of data subjects should be implemented, and regular testing to gauge compliance is a necessity.

On the security front, under the GDPR, organizations must implement “appropriate technical and organisational measures when it comes to guarding data.” Precisely what is deemed “appropriate” is not specified. Based on current guidance, the general rule regarding what suffices from a security perspective revolves around the best practices within an organization’s sector and “reasonableness.” A balancing test that analyzes the nature and sensitivity of data under inventory, as well as the associated risk profile, is prudent. For example, a financial institution or healthcare provider should undertake much more stringent security measures than a CPG brand, as the former sector has a higher risk profile.

Another focus area for analysis that is central to the proper implementation of policies and procedures relates to data inventory and flow. The data audit process outlined below is an essential first step toward having organizational data security that is in line with both best practices and global regulatory requirements.

- The first step for conducting this analysis is knowing what data your organization collects and has in inventory. This generally includes varying types of customer and employee data.

- Establish the lawful basis for the collection and processing of data. For example, some data processing may be done based on consent. In contrast, other inventory may be based on an agreement with a 3rd party vendor that has a legal basis to share data with your organization.

- Identify how inventoried data is used. Data’s potential applications are numerous, but the most common areas are marketing, R&D, and organizational management activities such as human resources.

- Document where and how data under inventory is stored. This includes the physical location of the data, the method of storage, and the format. The data may be stored in the cloud, managed by a vendor, or managed in-house and saved on the organization’s servers.

- Understand who has access to specific data within the organization. How is access segmented? Are there security measures in place to promptly identify suspicious access? Ensuring that access is granted in a strategic and controlled manner goes a long way toward mitigating risk.

- Timelines and actionable policies concerning the length of time that data is stored before being deleted are integral to a comprehensive data security program. Retaining data that no longer serves a business purpose is an area of increased scrutiny by regulators. They view such practices as an unnecessary risk, and we see a ramping up of enforcement aimed at discouraging it.

Reporting Requirements

Under the GDPR, there are reporting requirements that come into effect in the event of a data breach. Specifically, Article 33 requires a data controller to notify the relevant regulatory authorities within 72 hours of becoming aware of a breach involving protected PII that “is likely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals.”

The notification requirements are as follows:

- A description of the breach’s nature, including the categories and the approximate number of data subjects and personal records impacted.

- The name and contact details of the data protection officer or other people from whom more information can be obtained.

- A description of the likely consequences of the breach.

- A description of the measures taken or proposed to address the breach, including measures to mitigate its adverse effects.

Importantly, the notification requirement only comes into force if there is a breach that “is likely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals.” The “likelihood threshold” allows for some discretion in terms of differentiating between an incident where an intrusion of some sort may have occurred, but no protected PII was accessed, and therefore, notification may not be required. Making the distinction can be significant because once reporting becomes required, organizations are dealing with a tight 72-hour timeline that may involve a significant allocation of resources.

EU-US Data Transfer Mechanisms

An ancillary value of data beyond some of the most common uses relating to enhanced marketing and business intelligence is its ease of movement and transfer between partners, subsidiaries, and third parties. While such transfers are attractive for organizations, they are also an area that regulators have identified as rife with potential abuse and risk. One of the main issues when examining data transfers concerns the practices of the transferee organization.

Exemplifying the challenge concerning data transfers is best accomplished in the international context. For example, a business in Germany subject to the EU’s stringent GDPR is embarking on a transfer of PII to an organization located in the USA, which, in comparison, has historically had markedly less stringent obligations. The question for regulators in the EU is how to ensure that the transferee (American company) will protect transferred data in a manner that meets muster under the GDPR.

Privacy Shield Ruled Invalid (Schrems II)

To mitigate the challenge of GDPR-specific data transfers, the EU-US Privacy Shield was created. It was considered an “adequacy decision” by the EU. However, in July 2020, in response to a legal challenge, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled in the Schrems II case that the EU-US Privacy Shield was not valid. The ruling noted that United States surveillance laws allowed for intrusions that did not meet the protection thresholds required under the GDPR.

Following this, organizations primarily relied on Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) for international data transfers to the United States. New SCCs came into effect on June 27, 2021, and organizations had until December 27, 2022, to implement these into existing contractual arrangements.

EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework

On July 10, 2023, the European Commission adopted an adequacy decision for the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF). The DPF allows personal data to be transferred from the EU (and broader EEA) to U.S. companies that certify their adherence to a set of privacy principles. The DPF aims to address the concerns raised by the CJEU in the Schrems II decision. U.S. companies can self-certify their participation with the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Other mechanisms like Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) remain an option for multinational organizations, though they require approval from the relevant DPA.

The GDPR Has Teeth

When regulators, formerly known as the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (now called the European Data Protection Board or EDPB), were drafting the GDPR, one of the top priorities was to ensure that penalties were severe enough to discourage even the largest companies from non-compliance. To that end, under Article 83 of the GDPR, a maximum fine of €20 million or 4% of global turnover (whichever is higher) can be imposed. In the context of large corporations such as the internet giants, the 4% ceiling can amount to billions of dollars. Simultaneously, for smaller organizations, the €20 million fine can be more significant than 4% and acts as a significant deterrent.

When deliberating on whether and how much of a fine to impose, regulators have significant discretion. Furthermore, because each EU member state has its own data protection regulatory agency, there has been significant variation in enforcement and the related imposition of fines between EU countries, as well as tension. This discretion is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it is positive that supervisory authorities are directed to consider each scenario’s proportionality. They take into account the extent of failure to comply and any mitigating circumstances, including the presence of a good faith effort to achieve compliance. At the same time, the selective enforcement and unclear benchmarks translate into a situation where an organization that may be politically unpopular is penalized to a higher degree in comparison to its similarly situated peers who may have better favor with the public and regulators. Exacerbating the fractious nature of enforcement is the fact that each EU nation’s DPA has the power to regulate and penalize companies in their jurisdictions, known as the “one-stop shop” enforcement mechanism. EU nations without the presence of a company cannot prosecute. For this reason, Ireland has outsized power and influence since many of the largest tech companies have their European headquarters there.

To achieve a more uniform enforcement landscape under the GDPR, we have seen supervisory authorities across the EU attempt to coordinate with each other. For example, the Dutch data regulators outlined the structure they use in calculating fines for not complying with the GDPR. In summary, the Dutch DPA categorizes violations into four tiers. The first tier relates to the least egregious violations, while the fourth tier relates to the most serious ones. The categories are gauged based on the seriousness, nature, and extent of noncompliance. Though there is still much room for regulatory discretion in this structure, it does offer a more defined enforcement framework. We expect more clarity concerning enforcement as time goes on, as there is an imposition of more fines and associated case law formation.

Since the implementation of the GDPR on May 25, 2018, billions in fines have been imposed, with notable actions including a significant fine against Amazon by Luxembourg for alleged violations concerning consent for targeted advertising. Similarly, CNIL, the French DPA, has fined major tech companies like Google and Facebook for issues related to transparency and consent.

Going forward, we see a broad consensus among privacy professionals that there will be continued robust enforcement. Therefore, it should be imperative for organizations to assess for any lapses in their GDPR compliance regimens and take steps to remediate them effectively.

Free Speech & Other Challenges

With the sweeping rights afforded to individuals under the GDPR, there has also been a wide array of difficulties brought to light. One of the most prolific of these is free speech, which clashes with the right to erasure (also referred to as “the right to be forgotten”). The right to erasure, after all, is a core tenet of the GDPR. Though protections for freedom of speech are not as broad in the EU as in the United States, there are still protections for free expression. The most glaring example of a clash between speech and erasure relates to news and articles that disclose protected PII. The right to be forgotten is regularly used to request the removal of information. As things stand, it is often unclear where the boundaries between free speech and privacy lie and how they can be reconciled.

There are numerous other concerns about the abuse of the rights afforded to individuals under the GDPR. The right of access, which gives individuals the ability to obtain a copy of their PII, is an area prone to abuse. The most common form of such exploitation concerning the right of access is where a bad actor manages to get a trove of data on an individual under false pretenses, such as through impersonation, or where it is used as a negotiation tactic by disgruntled consumers or ex-employees.

The GDPR has created a multitude of niche challenges as well. For example, the Domain Name System (DNS) and the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) are used as a directory to access website ownership information (WHOIS). Due to GDPR, much of this information, previously useful for IP and brand management, is no longer as readily available. This change has resulted in a more drawn-out and complicated process for those looking to enforce their digital sphere rights.

The hope related to these challenges is that there will be greater clarity from the relevant regulators. There is a reason for optimism as we see regulators increasingly forthcoming by offering nuanced opinions vital for successfully conducting business operations with a sense of confidence.

Compliance Costs & Unintended Consequences

Estimates relating to the cost of compliance with the GDPR vary. There is no question, though, that the amount of time and resources expended is tremendous. To illustrate, reports indicated that Microsoft had 1600 engineers working on compliance, and Google spent hundreds of years of employee time on the GDPR, yet it still incurred hefty fines. According to the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP), 500,000 EU organizations registered data protection officers (DPOs) within the first year since the GDPR went into effect. Further, according to an IAPP survey, the average DPO’s salary in Europe was $88,000. These numbers help to underscore the astronomical costs that GDPR inflicted initially, and compliance remains an ongoing expense.

Connected to the cost of compliance is the concern that larger companies can use their vast resources to comply. In contrast, smaller companies may be disproportionately negatively affected since they lack the necessary funds. Initial reports after the GDPR went into effect suggested that some larger players gained tracking share, while smaller players experienced a drop. In short, independent players, especially in the ad tech sector, faced challenges competing with the scale and ability of internet giants. The result of this divide was, for some, a decrease in business, and in some cases, GDPR was cited as contributing to the shuttering of businesses.

Besides resources expended for compliance, some argued the GDPR also stymied innovation and associated investment. An early study suggested that venture capital investment in the EU fell following the GDPR’s rollout. In the world of M&A, an early survey indicated that a significant percentage of respondents stated that deals they worked on failed due to complications and concerns relating to GDPR compliance. Scientific research was also reported to be negatively affected due to restrictions imposed by the regulation, especially since data plays an increasing role in understanding and treating diseases. These remain areas of ongoing discussion and analysis.

Post-Brexit – Differentiating Between The EU’s GDPR & the UK’s GDPR

After Brexit, where in January 2020, the United Kingdom withdrew from the EU, it is necessary to differentiate between the EU’s GDPR and the UK’s GDPR. By and large, the two frameworks are very similar, as the UK incorporated the GDPR into its domestic law (now known as the UK GDPR). However, there are differences, such as the enforcement and regulatory agencies (the ICO in the UK), specific guidance, and how international data transfers are handled, particularly concerning adequacy decisions.

GDPR Going Forward

Taking a forward-looking view of the GDPR by using the guidance of the past is beneficial. To date, we have seen regulators employ a range of enforcement tools, not just fines. Proactive engagement with regulators can be beneficial. With that said, as supervisory authorities continue their work and investigations mature, we can anticipate continued enforcement actions. We also expect to have more case law and guidance developed as the GDPR continues to be interpreted and applied. Understanding these developments is crucial for maintaining compliance.