The Dynamics of Data Breach Response Law

Just the thought of a data breach or other similar attack on company systems is enough to make the CEO of a company shudder. After all, in our ever-increasing data-first world, breaches and attacks not only cause immense financial and reputational damage but also have the potential to bring operations, including those of a “mission-critical” nature, to a standstill. Compounding the challenge is the fact that the march of technology is relentless, and the threat landscape is constantly evolving and omnipresent. Therefore, what worked only a short time ago on the defense and mitigation front may no longer be effective.

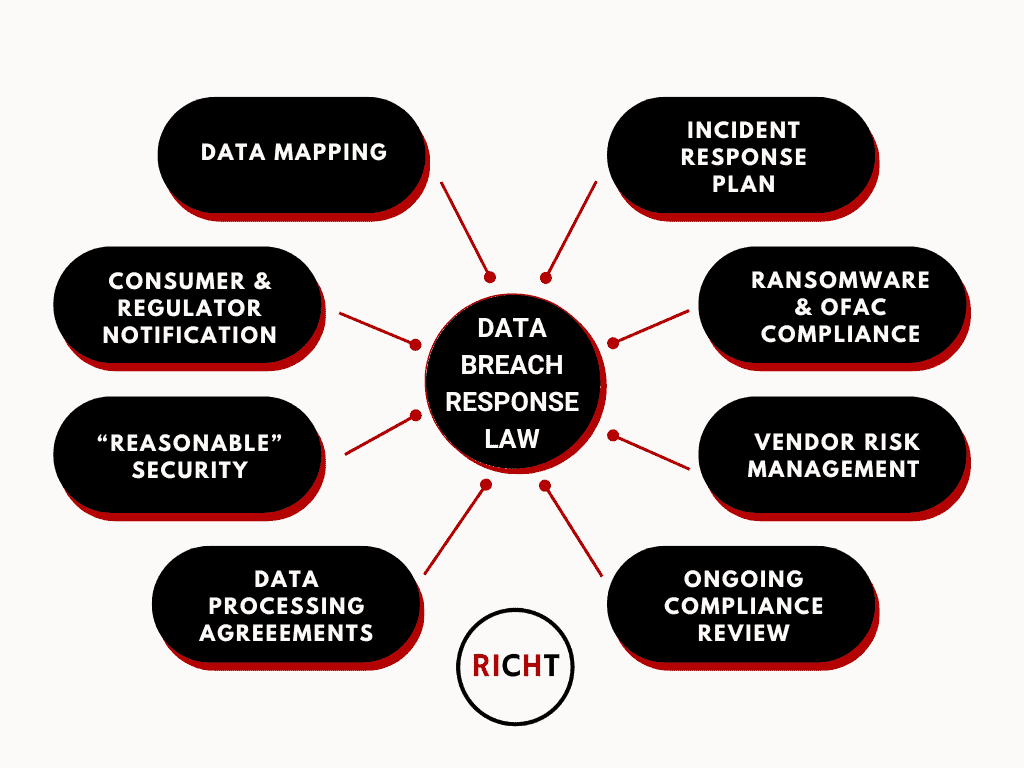

This discussion focused on the multifaceted nature of data breaches, incidents, and associated threat response with an emphasis on the intersection of the technical components of a holistic program with regulatory requirements and related considerations. Throughout, is important to underline that due to the ever-changing dynamics of threat actors, it is critical to be mindful that preparation and response are not monolithic; rather, it is an evolving journey that traverses distinct phases, each laden with unique challenges and considerations that will vary depending on the specifics of a particular organization. Take artificial intelligence (AI), for example. Many believe that the threat landscape has been upended by AI. While defense can be aided by such technologies, threat actors are also using AI in inventive ways, translating into further risk to organizations of all sizes and in all sectors.

First and foremost, we explore the realm of preparation, a proactive phase where organizations arm themselves with the tools, policies, and strategies necessary to mitigate risks and, if necessary, respond effectively. The intricacies of preparation span to include data mapping, robust cybersecurity measures, and well-defined incident response plans (IRPs).

Next, we delve into the active response phase, where an organization faces the crucible of the often high-pressure environment accompanying real-time incident management when time is of the essence. This phase is characterized by the rapid mobilization of resources, forensic investigations, and legal counsel with a focus on navigating the delicate balancing act of analyzing and containing a breach while maintaining stakeholder trust.

In addition to these pivotal phases, we turn our attention to the legal and regulatory considerations and requirements that loom over every data breach response. In an increasingly regulated environment, organizations must navigate a complex web of laws and standards, which vary from region to region.

As we journey through these distinct but interconnected aspects of data breaches, threat response, and the legal considerations throughout, we shed light on the evolving landscape of cybersecurity and the critical importance of preparedness, agility, and legal compliance in an age where data breaches are not a matter of if but when.

It All Starts With Data Mapping

As the amount of data being amassed by companies grows exponentially, the importance of data mapping becomes increasingly critical. It is now practically impossible to keep abreast of the immense data under inventory and the associated compliance obligations owed, ranging from data security to breach response, unless an organization has a real-time and comprehensive data map.

So what is data mapping, and how should an organization navigate accomplishing what can be an often disjointed but invariably ongoing process?

Data mapping, in the most simplistic terms, refers to documenting in a comprehensive manner the data that an organization processes. In the context of privacy and data security, data processing (subject to nuanced variations between legal frameworks) is inclusive of everything from initial collection all the way to storage. In essence, the goal of data mapping is to document and account for any informational gaps in an organization’s data processing by linking data fields in and from different sources to each other and consolidating it all into a singular “source of truth.”

An effective data map is one with data integrity, which translates into being a reliable source so that an organization knows where data currently resides and why, where it originated from, what format the data is in, its classification, and what lawful basis the enterprise has for processing it, among other variables.

There are various tools one can use to conduct data mapping. Some are “out of the box” solutions, such as from vendors like OneTrust and TerraTrue, while others are more rudimentary and not advisable for large organizations, such as trying to accomplish mapping via spreadsheets. Regardless of the tools used, the key principles for a best-in-class data mapping operation remain the same.

The principal goals of a data map are to identify and document the varying processing activities an organization undertakes, pinpoint data flows, and align the sources of the data with the destination. Mapping data flows identifies data relationships and their implications and creates clarity on responsibility and accountability at every step of the data processing operation. For example, organizations should know who has access to the data, how they are storing, sending, or sharing the data, and the rationales for each, including the lawfulness. Further, assessments, security, and mitigation, especially for “higher risk” processing, play a role in the data mapping process, too.

The Key Challenges Of Data Mapping

One of the biggest challenges when it comes to gathering the required information for data mapping is that it often requires complex coordination of varied teams within an organization and, in some cases, external parties such as vendors, as well. In order for the data map to “have integrity,” diverse teams spanning operations to marketing and everything in between need to be committed to devote time and resources to work with the relevant privacy and security teams to comprehensively outline processing activities and associated details that are essential for a data map.

Besides the commitment of resources, another challenge concerns unknown data processing and, in particular, storage. After all, getting everyone together in many companies is challenging, to say the least, and therefore oftentimes, companies resort to emails and spreadsheets to collaborate. Additionally, employees may unilaterally decide to process data with good intentions, such as testing out a new idea. This setup is ripe for “data sprawl,” which refers to the unaccounted-for spread of data, sometimes even sensitive data, to multiple systems in an unaccounted-for manner, an untenable and risk-prone position.

Keeping data maps current is another key pain point. Since processing activities are dynamic, both in terms of the vendors and systems used but also in the type and scope of data processed, data maps need to be constantly updated to reflect these changes. It is common for a business line or department to make such changes without accountability or notification to the point of contact spearheading data mapping. The result is outdated data maps that do not provide accurate pictures of an organization’s processing activities. The knock-on effect of such a scenario is significant and ranges from inadequate breach response posture to deficient legal compliance measures.

The solution to these challenges is not easy but revolves around the commitment of resources and training. At the end of the day, the importance and legal necessity of data maps need to be stressed and made a priority. Further, processes and systems should be implemented, and regular training given on the standard operating procedures (SOPs) to follow when a processing activity is initiated or materially changed so that data maps are updated accordingly. Further, the risks of “rogue” data processing need to be spotlighted regularly.

The Laws Mandating Data Maps & The Practical Purposes They Serve

The necessity of data mapping and, by extension, the value it provides, particularly on the visibility and accountability fronts, including as it relates to the data the organization is processing and ultimately responsible for, is further underlined by the trend of privacy laws mandating data maps. Whether it be the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or one of the many states in the United States that have recently passed comprehensive privacy laws, such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), data mapping and associated assessments play a leading role in underpinning a holistic privacy program.

To illustrate, under the GDPR, as per Article 30, companies must maintain a record of all processing activities (ROPAs), including the purpose of processing the data, legal bases, consent status, and any cross-border data transfer. Moreover, data mapping is an essential prerequisite to complying with many other seemingly unrelated sections of the GDPR. For example, under Article 35, for certain, more risky or sensitive processing, companies must conduct data protection impact assessments (DPIAs). This is only possible if the categories of data in their possession and the types of processing undertaken are clearly documented and can thereby be analyzed for potential escalation to a DPIA. Data maps are also useful in ensuring compliance in responding to data subject access requests (DSARs) and other privacy rights, an increasingly common component of privacy operations and overall compliance.

In addition to the GDPR, practically all the states in the United States that have comprehensive privacy laws, as well as many countries that have passed similar regulations, have some form of data mapping requirement, as it is an essential piece of the compliance puzzle. That said, the requirements are evolving on a regular basis. For example, the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) released its initial draft regulations for cybersecurity audits and risk assessments in 2023, and other state agencies are tasked with releasing similar regulatory guidance under their respective privacy regulations.

Vendors Are A Significant Risk Vector

Vendor risk is a critical component to account for in the context of data breach preparedness and response. After all, vendors are a significant and common vector of risk. According to a recent report, approximately 62% of data breaches are the result of vendors of various types, ranging from software providers to outside consultants, which have been the weak link that made immensely damaging breaches possible.

Vendors and associated risks are also intimately related to the previous component of breach preparedness discussed, data mapping. Generally, as part of the onboarding of a new vendor, a security audit in combination with a mapping of any processing that will take place as part of the vendor services performed. Though the exact dynamics of how such vendor risk assessment is performed vary by organization, when done correctly, the assessment and data mapping act as a key “checkpoint.”

Essential Steps to Minimize and Mitigate Vendor Risk

In light of the considerable risk posed by vendors, at the outset of a business line within an organization expressing interest in engaging a vendor, the vendor risk review process should be initiated. Optimally, this process involves both security and privacy teams, who work collaboratively to ensure that risk is accounted for and mitigated accordingly. A key part of this process is the data mapping component discussed in depth previously. Other considerations relate to contracting, such as ensuring data processing agreements (DPAs) that are comprehensive and compliant are implemented. Further considerations range from ensuring adequate insurance and indemnification by the vendor, proper data security (both technical and administrative safeguards), breach response plans and notification timelines (including roles and responsibilities), and audit rights, among other critical clauses.

Threat Actors Come In Varying Forms & Are Continuously Evolving

The threats coming at an organization are continuous and evolving regularly and underline the “always on” mentality that has to be fostered in orderr to stay at the cutting edge of the threat landscape and avoid complacency.

It is helpful to overview some of the most notable recent attacks to illustrate the broad range of threat actor types.

“Traditional” Attackers

“Tradtional” threat actors are the ones that come from outside the organization and are looking to make money either through ransomware or some other monetization strategy. In an attack on Clorox, hackers damaged their IT infrastructure, causing product shortages and disrupting supplies and operations for over a month. Many of their automated systems had to be taken offline, forcing them to process orders manually. The loss in revenue as a result of the attack is estimated at well over 500 million.

Insider Threats

In contrast to threat actors from outside an organization, who can often be more easily defended against, insiders who pose a threat for nefarious attack are more elusive in many ways. After all, they are “within the city gates.” These insiders can have varying motivations and come in different forms. They can be a disgruntled employee or a trusted vendor and could be driven to simply cause damage or see financial gain.

In a breach involving Capital One, files containing the personal information of about 100 million people were stolen from Capital One servers and posted on GitHub by a former systems engineer of Amazon Web Services. As an “insider threat,” the individual knew how to navigate the infrastructure and take advantage of the misconfigurations. This attack stresses that insider threats include those of third parties, such as cloud vendors.

State Actors

Nation states seeking to attack an organization are powerful foes, after all they have the immense resources that only a state can muster. For context, in 2017, Foreign Policy estimated that China’s “hacker army” ranges from 50,000 to 100,000 personnel, and experts believe it has grown significantly since. Even the largest of the technology behemoths are challenged by the sheer size and, by extension, brute force capabilities of such actors. As an example, In 2018, Marriott was attacked by what was alleged to be China and managed to exfiltrate about 500 million guest records, including sensitive information like passport numbers. It is believed that the motivation for this attack was to gain valuable information on potential intelligence targets, including for counter-espionage. The more novel motivations for nations performing attacks make it significantly more challenging to telegraph vulnerabilities.

Another related particularly pertinent consideration in the context of attacks by state actors is cyber insurance coverage, and whether an attack of such nature is not included.

Other Threat Actor Types

In addition to hackers seeking monetary gain, insiders, and nation-state actors, there are a variety of other threat actor types, such as organized crime rings and “hacktivists.”

Common Attack Techniques & Systems Targeted

After understanding common threat actor types and their potential motivations, it is also necessary to understand the techniques they utilize to perpetrate attacks and the kinds of systems they target.

Common Attack Techniques Utilized

Phishing & Business Email Compromise (BEC)

One of the most successful attack vectors is phishing. Phishing comes in different forms, including “spear phishing,” but generally centers around sending emails while impersonating a reputable entity aimed at inducing the recipient to take action. Relatedly, business email compromise (BEC), involves spoofing or compromising email accounts of employees, often those in a decision-making capacity, such as the C-Suite, in order to instruct others to make fraudulent money transfers.

Brute Force Attacks & Credential Stuffing

Brute-force attacks involve attempting every combination of characters to guess a password. Similarly, credential stuffing involves using a known username and password pair against other websites.

Zero-Day Exploits

A zero-day exploit occurs when an attacker discovers and exploits a software vulnerability before the vendor becomes aware of its existence. Software patches are constantly being released, and ensuring timely updates is critical for keeping attackers out of systems.

Malware & Viruses

Malware and viruses come in a wide range of forms, including as they relate to their end goals and the means such software uses to accomplish said goals. The code can be aimed at disruption, data extraction, keylogging, or gaining unauthorized access to or control of various systems.

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks

Distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks aim to overwhelm servers or systems with unusually high amounts of traffic, rendering them unable to perform their function and, at times, compromising them.

Data & Systems Commonly Targeted

The types of data and associated systems most commonly targeted are broad-ranging and not always obvious. On the enterprise side, the most obvious targets include company critical systems, intellectual property, and, in particular, trade secrets, including source code. When it comes to the consumer, including companies that have vast amounts of consumer personal data, sensitive personal information of high risk for targeting includes payment data, social security numbers (and related government-issued identification), and health data. Examples of less obvious data points targeted, such as in the context of travel records sought by state actors for intelligence gathering, illustrate the challenges of protecting the full spectrum of data beyond just the most obvious “crown jewels.”

Breach Response

In order to properly respond to a breach, a comprehensive incident response plan (IRP) must be formulated, continuously tested, and optimized to reflect a constantly changing threat environment. A proper IRP will be holistic and include components ranging from technical forensics and containment to communications professionals and legal counsel.

Forensic Analysis

Immediately upon finding out that there may have been an incident of some kind, an organization should make it a priority to put its IRP into full gear. After all, time is of the essence when it comes to incident response. The reasons for the swift response are varied. For one, it is possible that damage can be controlled by limiting the intrusion through technical means and ensuring that more damage is not done. Further, there are tight regulatory timelines that need to be followed under varying breach notification legal frameworks.

The first step in digital forensics incident response (DFIR) is to determine the specifics of the incident. To do this, experts collect data from compromised systems and then analyze it carefully to find indicators of compromise. Next, an in-depth investigation is performed to discover evidence and identify existing threats. All information should be documented and preserved, while the actual examination should generally only be performed on a forensics copy. The focus of the investigation should be on finding tracks left behind by the attacker and piecing together a timeline of the incident as well as the extent of any damage, including whether the systems are still compromised and the extent of any data exfiltration. Further, forensics work helps to ensure that lapses in security are fixed so that future incidents are avoided to the greatest extent possible.

In addition to getting a technical understanding of an incident via forensics, knowing what the goals of the threat actors are can be very beneficial, too, though it is not always obvious. For example, when dealing with ransomware, it is clear from the outset that money is being sought in return for what is often systems access or promises of data destruction. Granted, there are more complex questions that arise in the ransomware context, such as concerning the threat actors’ reliability as well as whether payments may be in violation of OFAC sanctions. But at least the motivation is clear and the goals more predictable. In contrast, when it comes to nation-state actors, the damage is not always apparent, and the motivations are unclear, leading to an often more challenging analysis of the true extent of the damage.

“Incident” Vs. “Breach”

One of the foundational questions that has to be answered once some sort of intrusion is discovered concerns whether the event is classified as an “incident” or a “breach.” While the distinction may seem trivial to some, the consequences between the two are significant, and differentiation is critical. At the most basic level, an incident is an intrusion of some kind into an organization’s systems, whereas a data breach involves something more than just an intrusion and generally includes access, disclosure, modification, or destruction of the data. Perhaps most notably, on the regulatory front, incidents are treated with less scrutiny and overall fewer compliance obligations than data breaches. In light of the more lenient treatment, it is no wonder that organizations prefer to classify an event as an incident and not as a breach. That said, the analysis of the facts, including forensics, is key to ensuring that the proper classification is made, including concerning the corresponding applicable data breach regulatory framework. Laws will differ about how they diffrentiate between incident and breach, and therefore, understanding which laws apply in each scenario is critical. To illustrate, in the context of Protected Health Information (PHI) that is subject to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) states:

An impermissible use or disclosure of protected health information is presumed to be a breach unless the covered entity or business associate, as applicable, demonstrates that there is a low probability that the protected health information has been compromised based on a risk assessment of at least the following factors:

- The nature and extent of the protected health information involved, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification;

- The unauthorized person who used the protected health information or to whom the disclosure was made;

- Whether the protected health information was actually acquired or viewed; and

- The extent to which the risk to the protected health information has been mitigated.

With the HHS’ guidance, an organization can leverage its forensics to make the case that an intrusion was not a data breach if the facts point that way. That said, if the facts and circumstances signal in the direction of a data breach, intentionally misclassifying is not a wise route to pursue.

Attorney-Client Privilege In The Context of Breach Response

Maintaining attorney-client privilege and confidentiality is paramount in preserving the trust essential for effective legal counsel in the context of a data breach response. Further, when orchestrated correctly, third parties involved in breach response activities, ranging from forensic experts to public relations professionals, can be within a crucial extension of the attorney-client privilege umbrella, ensuring that the information shared remains protected. The means to extend this protection is via a Kovel Agreement, based on the seminal case of United States v. Kovel, which recognized the extension of attorney-client privilege to non-attorney consultants in specific scenarios. Applying Kovel Agreements helps maintain the confidentiality of communications with these experts, safeguarding sensitive information from exposure. Preserving attorney-client privilege through mechanisms like Kovel Agreements not only assists with any future legal defense but also encourages a collaborative and secure environment for navigating the complexities of breach response. It is important to note, though, that adequately structuring the engagement and dynamics of the relationship with the third party is critical in order to be protected under Kovel. In specific scenarios, courts have deemed “Kovel-type” arrangements lacking and, therefore, not subject to privileged treatment.

Breach Notification

In tandem with diagnosing the facts and circumstances of an incident and limiting the damage via forensics and related response, the need for notification of any relevant regulators and law enforcement, as well as affected consumers (referred to as “data subjects” in certain jurisdictions) needs to be a prioritized consideration. Depending on the scenario, and in particular, when the breached party is a vendor to other businesses, notification to parties whom the vendor services will also be necessary. In such a vendor scenario, the dynamics of who will perform the required notifications of consumers will also come into play.

All fifty states (plus territories), as well as most countries, including those in the European Union and the United Kingdom operating under their respective versions of the GDPR, have some form of breach notification regulatory framework. Further, there are sector-specific overlays, such as in the case of a breach affecting Protected Health Information (PHI) and is, therefore, under the purview of HIPAA or certain financial entities regulated by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA). Other potentially relevant sector-specific regulators include the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Federal Communications Commission (FCC), New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS), and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). In light of the patchwork nature of notification regimes, it is critical to get a clear picture of the relevant regulations that apply in a particular scenario, including any relevant thresholds of affected individuals to trigger a particular breach notification obligation, as well as an analysis that accounts for the dual considerations of consumer location(s) as well as information type. Depending on the extent of the breach, several, if not all, state breach notification regimes might be in play, as well as sector-specific and federal notification, not to mention notification to international regulators, such as if a breach involves EU or UK data subjects.

Gaining a comprehensive understanding of breach notification obligations for a breach, even a relatively small one, can be overwhelming since each law has its own nuances and requirements, not to mention the tight turnaround timelines where notification must be made. Oftentimes, the “fog of war” is still in effect, and the extent of an incident is still being evaluated. The details to be included in letters to affected consumers as well as in reports to regulators need to maintain a balance of telling the truth but not unnecessarily adding to the potential for liability, in particular in the event of future litigation or enforcement. It is common for updates to be made to initial regulator notifications in order to maintain an accurate record of the breach as the investigation progresses and additional details may be discovered.

On the topic of breach notification, especially on the consumer side, regulators have been particularly irked by promises of credit monitoring or other identity protection claimed to be offered for certain periods that were, in reality, less than what was claimed. This is another example of the additional risk vectors that arise as a result of a data breach and the reality that suddenly, an organization’s every move is under the microscope. It is, therefore, critical to navigate data breaches being cognizant of the extra scrutiny and to make every effort to “dot i’s and cross t’s.”

Lastly, though we previously comprehensively discussed the value of data mapping in the breach response context, it is appropriate to stress how holistic data maps are invaluable in implementing a more streamlined breach notification procedure, as the affected parties and compromised data can be more easily identified and analyzed.

Preparation & The Importance of Reasonable Security

There is a common maxim about data breaches that “it is not a matter of if but when” a data breach or related incident will occur. With that as the baseline, the goal is to prevent incidents from occurring and, when they inevitably do occur, to limit the amount of damage to the maximum extent possible.

As we overviewed in previous sections, the amount of damage and resulting cost from data breaches can be immense, and another expression, that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” could not be more apt.

When aiming to prepare and defend an organization’s systems, including via technical and administrative safeguards as well as comprehensive IRPs and cyber insurance, the importance of reasonable security should be stressed. Increasingly, laws, including but not limited to the recent proliferation of comprehensive state privacy laws, have included provisions that require certain foundational levels of data security. Further, there are other laws, such as New York’s SHIELD Act, which has reasonable security as the key aspect of the law and has seen continued enforcement by the attorney general. Many other laws, such as the GLBA, and regulators, such as the SEC, mandate cybersecurity measures. The particularities of what is considered adequate or “reasonable” security will vary depending on the organization in question and, in particular, the types of activities they engage in. For example, a financial institution will have a higher level of baseline security to meet the “reasonableness” standard as opposed to a website that is only collecting names. Regardless though, ensuring “reasonable security” helps to mitigate against sizeable risk, in particular as it relates to private actions, such as under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA).

The Costs of Inaction

The costs of inaction when it comes to breach preparedness, including defense and response, are multitude and range to include losses from enforcement action and litigation as well as systems repair and reputational damage.

On the regulatory enforcement front, some of the most active agencies include the FTC, SEC, and state attorneys general and include the following examples:

- FTC announces settlement with Global Tel*Link and its subsidiaries for data security failures: Following its investigation, the FTC concluded that the companies had, among other things: failed to employ reasonable and appropriate measures to protect consumers’ personally identifiable information; failed to notify in a timely manner affected consumers that their personally identifiable information had been exposed as a result of an incident; misrepresented, directly or indirectly, expressly or by implication, that they implemented reasonable and appropriate measures to protect personally identifiable information against unauthorized access; and misrepresented, directly or indirectly, expressly or by implication, that they had no reason to believe that consumers’ sensitive personally identifiable information was affected by an incident.

- SEC charges SolarWinds and its CISO with fraud and cybersecurity failures: The SEC alleged that SolarWinds and Brown defrauded investors by overstating SolarWinds’ cybersecurity practices and understating or failing to disclose known risks. In its filings with the SEC during this period, SolarWinds allegedly misled investors by disclosing only generic and hypothetical risks at a time when the company and Brown knew of specific deficiencies in SolarWinds’ cybersecurity practices as well as the increasingly elevated risks the company faced at the same time.

- NY DFS announces $1 million cybersecurity settlement with First American Title Insurance Company: The New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) today announced that First American Title Insurance Company (First American) will pay a $1 million penalty to New York State for violations of DFS’s Cybersecurity Regulation (23 NYCRR Part 500) stemming from a large-scale cybersecurity breach in May 2019.

- NY AG fines Morgan Stanley for putting customer personal data at risk in computer purge: Morgan Stanley agreed to pay a fine of $6.5 million to a coalition of six states for compromising the personal data of millions of customers while decommissioning computers at the financial services giant, New York’s attorney general said.

Private actions are also common and, for example, include the following:

- MGM, Caesars face nine lawsuits in wake of cyberattacks: Two major casino-resort operators on the Las Vegas Strip now face a combined nine federal lawsuits in the wake of cyberattacks that exposed the personal information of thousands of customers and crippled the operations of one of the companies.

In addition to traditional enforcement measures, there has been a new wrinkle added to data breach and cybersecurity enforcement by the FTC and SEC, among others, in the form of imposing personal liability on executives, as was the case in Uber and Drizly, which caught most by surprise and has radically changed the risk balancing mix.

In addition to costs from regulatory enforcement or private actions, the reputational harm, including as it relates to value on the public markets, cannot be overlooked. To illustrate, Okta, a public company focused on identity management solutions, saw a loss of more than $2 billion to its market cap after it was the victim of a breach.

Looking Ahead

Data breach response and the law are an incredibly dynamic area, with new developments occurring on a practically daily basis. Whether it is a new best practice for incident response or a new law requiring particular action concerning breach notification, the one theme that is consistent throughout is that nothing is stagnant, and complacency is a recipe for disaster. Organizations need to take a comprehensive approach in preparing for eventual data breaches and ensure constant improvement and evolvement in tandem with the ever-changing threat landscape. From maintaining adequate cyber insurance to ensuring holistic and battle-tested IRPs as well as “reasonable” cybersecurity, the varying components critical for success are not always easy, but they are nonetheless essential. After all, the stakes are simply too high.